Queen of Angels began with one woman’s devotion to the Catholic faith (Black History Month)

Queen of Angels Parish was the first African American Catholic congregation in Newark, N.J., paving the way for interracial Catholicism throughout the Archdiocese and becoming a model of social and civil rights activism in the 1960s.

According to Knowing Newark, an online history of Newark African Americans, Queen of Angels’ history begins with a woman named Anna Theresa Lane. Lane, “a young colored nursemaid,” converted to Catholicism after recovering from a serious illness. Upon getting baptized at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York, she began seeking converts in Newark, eventually joining forces with a fellow Catholic named Lucy Milligan in 1926. Together they recruited 15 more women, mostly West Indians, who began attending their regular meetings.

Impressed with the women’s devotion to the faith, Newark Bishop Thomas J. Walsh established Queen of Angels Parish for African Americans on Sept. 30, 1930, on the feast of St. Peter Claver, who worked with Black people in South America. (Peter Claver, SJ was a Spanish Jesuit priest and missionary born in Verdú who, due to his life and work, became the patron saint of slaves, the Republic of Colombia, and ministry to African Americans. ) Father Cornelius J. Ahern, the curate of St. Joseph’s Parish in Newark, was appointed to head Queen of Angels, which met in the basement of St. Bridget’s Church.

Father Robert James Wister, Hist. Eccl.D., of Seton Hall University, wrote in The Catholic Historical Review that Black Catholics, few in the 1920s, were almost invisible in the Newark diocese until Lane and Milligan’s group became active.

“Father Ahern immediately implemented a series of religious, educational and welfare programs, and in one year the church grew from 62 to 360 parishioners. A portable structure at Wickliffe and Academy streets was built and its devotions on Thursday evenings were attended by a large number of white supporters and friends who helped create a much-needed spirit of interracial support,” according to Knowing Newark.

“Soon, the new parish earned a reputation for its excellent choir, congregational singing, and marching band, which appeared at many community functions.”

In his review of “A Mission for Justics,” a book about Queen of Angels written by Mary Ward in 2002, Father Wister wrote that Queen of Peace in the 1930s reflected “an enlightened Catholic application of the Protestant ‘Social Gospel’ of the era, with parishioner participation in decision making.”

He credits Ward with clearly describing “the complexity of the Black community of 1930s Newark, the status-conscious Protestant Black churches, and the community’s relationship with various city offices and civic organizations.

“In this, Queen of Angels behaved more like a Protestant church than a very docile Catholic parish,” Father Wister wrote.

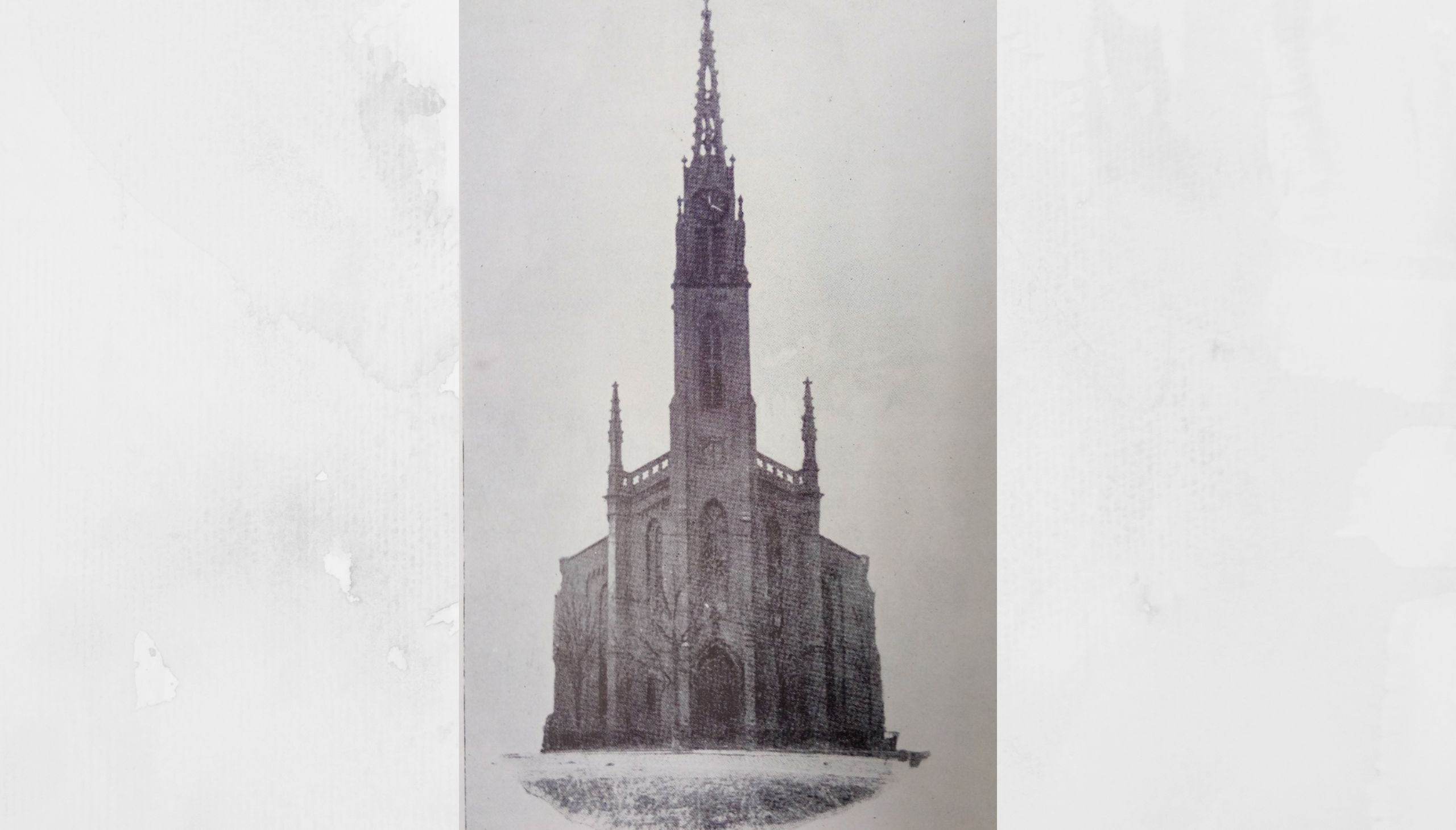

When it moved to an old church known as St. Peter’s on Belmont Avenue (now Irvine Turner Blvd) at Morton Street in the 1960s, Queen of Angels became vital in the civil rights movement. Martin Luther King Jr. held meetings there for the Poor People’s Campaign before his assassination. The parish also helped organize a march for racial harmony when he was killed.

“The reach of Queen of Angels extended far beyond its own membership. For example, while riots erupted in other cities across the country after the murder of Martin Luther King Jr., Queen of Angels played an instrumental role in organizing the Walk for Understanding, a peaceful march of 25,000 blacks and whites through the heart of the inner city,” according to a review of Ward’s book on University of Tennessee Press. “That event and the ethos that inspired it gave birth to the New Community Corporation, the largest nonprofit housing corporation in the country, led by former Queen of Angel’s priest, Father William Linder.”

By the 1960s, many community members looked to Queen of Angels as a model of social and civil rights activism. The parish became so culturally significant that it was eventually added to the National Historical Registry. However, according to the Digital Archives of Newark Architecture, the church was demolished in 2016 after the building deteriorated and the parish’s membership declined.

Father Wister told Jersey Catholic that the spirit of the parishioners of Queen of Angels lives on in the chapel of Immaculate Conception Seminary at Seton Hall University.

“A few years ago, the chapel was extensively renovated. Stained glass windows from Queen of Angels were restored and placed in the chapel,” he said. “Also, the pews of Queen of Angels were refurbished and placed in the chapel.”

Afterward, Msgr. Joseph Reilly, Rector, invited former parishioners of Queen of Angels to the seminary for a memorial mass in the chapel and a reception.

“The people were delighted to see the windows and pews that brought back memories,” Father Wister said.

To learn more about Queen of Angels Parish, read “A Mission for Justice: A History of the First African American Catholic Church in Newark,” which is available on Amazon.

Featured image: Queen of Angels originally started out in the basement of St. Bridget’s Church in 1930. After St. Bridget’s was destroyed in 1958, Queen of Angels relocated to a church once known as St. Peter’s. (Photo: NJchurchscape.com)