Remembering St. Anthony’s Mission House, a 1920s integrated US Catholic seminary (Black History Month)

About 101 years ago in October, a Catholic religious community in the United States did what (almost) none other had done before: they opened an interracial seminary on US soil.

The Josephites had attempted a similar effort in the late 19th century for their own mission, namely ministry to African Americans. Their minor (Epiphany Apostolic College) and major seminary, St. Joseph’s, in Baltimore were open to African Americans at their founding. Racism among the US bishops and within the Josephites would quickly lead to the cessation of this policy.

Most Americans with an interest in Black Catholic history have heard of the Josephites. However, the religious community that opened St. Anthony’s Mission House, in Highwood, N.J. in 1921 and then moved to Tenafly, N.J. is less well-known stateside despite its voluminous impact on the history of African-American Catholics.

Meet the Society of African Missions, founded in France by Venerable Melchior de Marion Brésillac to evangelize in the motherland, thousands of miles from the African diaspora in the New World. Founded in 1856, the society would touch base in America some 40 years later in an effort to raise funds for their fledgling missions.

The SMA property in Tenafly is a formation house and residence that celebrates liturgy and serves as the headquarters of the SMA’s American province. The property also houses the province’s African Art Museum. It is located at 23 Bliss Ave. Go to smafathers.org for more information on visiting.

Within a decade, however, they had begun ministry with Africans recently freed from slavery in the United States.

Consider one Fr Ignatius (Ignace) Lissner, the SMA priest who had first arrived in the US in 1897, and who later became infatuated with the idea of working for Black liberation stateside. A native of France, he had previously served in Africa, ministering in the Kingdom of Dahomey—think “The Woman King”—before being kidnapped by the ruling house and escaping in 1892. Following his first trip to North America five years later, he returned to Africa and served as a chaplain during the infamous British-Egyptian invasion of Sudan.

Reassigned to Georgia in 1901, Lissner again fundraised for the Society for five years before Bishop Benjamin Keiley, head of what was then the Diocese of Savannah-Atlanta, received word from the Vatican that the SMA Fathers should take charge of local Black Catholic ministry. (From their founding, the SMAs always had a provision to work outside of Africa, provided it was with people of African descent.)

A number of French priests soon arrived to take charge of St. Benedict the Moor Catholic Church in Savannah, and Lissner himself soon founded a number of Black churches and schools in the diocese, including Our Lady of Lourdes in Atlanta—this year a hundred years old, and one of the more well-known Black parishes in the Deep South.

In Savannah, Lissner also played a major role in the formation of the nation’s third-oldest surviving order of Black nuns, the Franciscan Handmaids of the Most Pure Heart of Mary, co-founded by Mother Mary Theodore Williams, FHM in 1916. The sisters would soon play their own role in Lissner’s future seminary.

At the time, in the early 20th century, the prospect of African-American Catholic priests remained bleak, with most dioceses—including Savannah—refusing to accept Black applicants to their seminaries. As already mentioned, even male religious communities dedicated to Black people were wary of the perceived dangers of allowing that community to serve itself in ordained ministry.

Lissner, however, was one of the few White Catholic men in America who felt otherwise and had the power to do something about it. And so he did, with Vatican approbation via the recently installed prefect of the Propaganda, Cardinal Willem van Rossum.

Following an abortive plan to open the interracial seminary in the South itself, and with funding from you-know-who—St. Katharine Drexel—Lissner acquired property in Bergen County, New Jersey to open St. Anthony’s, which was open to all races. (The previous year, the Society of the Divine Word had opened in Mississippi what would become St. Augustine’s, the nation’s first all-Black Catholic seminary.)

Bishop John J. O’Connor of Newark gave his blessing for Lissner’s new school, and the Franciscan Handmaids served there as domestics before their departure across the Hudson to Harlem, where they remain to the present day.

Restricted by SMA higher-ups in his recruitment of Black students for St. Anthony’s, Lissner nevertheless found a number of interested prospects, including Joseph A. John—an embattled Josephite seminarian who had found difficulty convincing them to actually ordain him—and William E. Floyd, who had also been in formation with the Josephites before being ousted. Both eventually entered St. Anthony’s and were ordained for the SMAs, with John becoming in 1923 the nation’s eighth openly Black Catholic priest.

Neither John, Floyd, nor a third African-American graduate of St. Anthony’s were ever fully accepted as ministers in the United States, however. Like the Josephites before them, the SMAs found that the nation’s bishops were unwilling to allow Black priests to actually serve in Black parishes—or any parish, for that matter. All three of the first Black SMA priests eventually left the society (and America) for the Archdiocese of Port-of-Spain in Trinidad.

Again like the Josephites, the SMA hierarchy was deeply disturbed by the developments with John, Floyd, and others. This would eventually spell doom for St. Anthony’s, which had moved to Tenafly, New Jersey but failed to attract many White applicants. Those who did come were nonplussed about studying alongside Black men, even in the “integrated” North.

Given all these factors, what began as restrictions for Lissner—limiting the Black men he could bring to St. Anthony’s—eventually became an outright ban. Soon after, the seminary was closed against his will in 1926.

Today, the SMA Fathers retain their property in Tenafly, which now serves as the headquarters of their American province, and the site of their local African Art Museum (a feature of their missions in various countries worldwide).

Lissner himself, who had spearheaded the creation of the province, went on to help found Black parishes and schools in the dioceses of Belleville, Los Angeles, and Tucson before his death at the St. Anthony’s property in 1948.

The society, with a much smaller stateside footprint than in those years, serves to the present day in the archdioceses of Newark, Boston, and Washington, DC, but no longer in the South where their US missions were founded.

The ongoing struggle for Black vocations continues across all religious communities and dioceses in the United States, and prospects for the future are unclear, to say the least. Fr Lissner, the SMAs, and St. Anthony’s Mission House, however, remain essential (though muted) features of that tale in its early years.

Venerable Melchior de Marion Brésillac, pray for us.

Nate Tinner-Williams is co-founder and editor of Black Catholic Messenger, a seminarian with the Josephites, and a ThM student with the Institute for Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University of Louisiana (XULA).

This article was originally published in Black Catholic Messenger and republished on Jersey Catholic with permission.

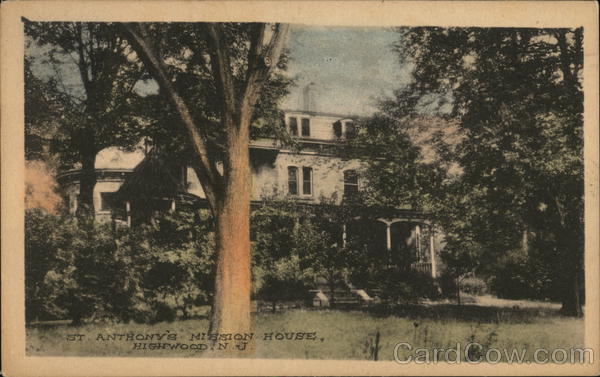

Featured image: St. Anthony’s Mission House, a racially integrated minor seminary founded by the Society of African Missions in 1921, at its original location in Highwood, Bergen County, N.J. (CardCow)