Panel: Civil Rights Act brought needed change but fight for equality, end of racism ongoing

It was June 1963, and President John F. Kennedy had just months to live before an assassin’s bullet would shatter his skull in the streets of Dallas Nov. 22, 1963, during a two-day, five-city Texas campaign tour.

But following a torrid spring and summer of U.S. racial tensions that included indelible images such as the Woolworth’s sit-in — when nonviolent activists stoically sat at a downtown Jackson, Mississippi, lunch counter while a jeering, pro-segregation crowd doused them with drinks, sugar, mustard and ketchup — Kennedy had promised the American public he would ask Congress to pass a civil rights bill by the end of the year.

It didn’t happen during Kennedy’s lifetime — but when the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was eventually enacted on July 2, 1964, America finally had a law aimed squarely at dismantling centuries of inequality by prohibiting discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. Unequal application of voter registration requirements was prohibited, as well as segregation of schools and other public facilities.

On June 4, a panel at Georgetown University in Washington — “The Civil Rights Act of 1964 After 60 Years: Challenges and Questions for Voters and the Nation in 2024” hosted by the Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life — gathered to assess both progress, and the problems that remain.

“Catholic and other religious communities played key roles in this effort, which offered hope to people who had been excluded from opportunities in education, housing, and employment, simply based on race, color, or national origin,” said Kim Daniels, director of Georgetown’s Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life, as she welcomed guests and introduced the discussion panel.

“And yet, of course,” added Daniels, “there is still so much more to be done.”

Kimberly Mazyck, associate director of the Initiative, who moderated the conversation, immediately addressed an uncomfortable historical truth.

“We must acknowledge that Georgetown University exists in part because of the proceeds of an 1838 sale of 314 enslaved women, children, and men,” Mazyck said. “As members of this community, we are indebted to them and their descendants for their stolen labor. We cannot ignore that history as we gather tonight.”

To fund the expansion of the newly Jesuit-founded Georgetown College, those 314 enslaved people were sold by the Jesuit Order to plantations in Louisiana.

Mazyck reminded listeners that, “Civil rights and racism are not abstract or historical issues.” Citing the current pontiff, she noted, “In ‘Fratelli Tutti,’ Pope Francis states, ‘Racism, when it retreats underground, only keeps reemerging. Instances of racism continue to shame us, for they show that our supposed social progress is not as real or as definitive as we think.'”

The Catechism of the Catholic Church states, “The equality of men rests essentially on their dignity as persons and the rights that flow from it: Every form of social or cultural discrimination in fundamental personal rights on the grounds of sex, race, color, social conditions, language, or religion must be curbed and eradicated as incompatible with God’s design.”

“I remember when the act was first proclaimed,” shared Sister Cora Marie Billings, a Sister of Mercy who was the first Black member of the Philadelphia community. “And at that time, I had already experienced the evil of racism.”

Sister Cora Marie led the Diocese of Richmond, Virginia’s Office for Black Catholics for 25 years, and her great-grandfather was enslaved by the Jesuits at Georgetown University. Among other memories, she recalled being denied holy Communion as a third grader in 1947; at 14, she was relegated to the back of her church, and made to surrender her seat if a white parishioner arrived.

“For me to have the bill,” Sister Cora Marie recalled, referring to the Civil Rights Act, “was a sense of hope — because maybe things would change. And the change for me will come — and we keep going with it — when we all together become relational, and make sure that we are working at it together, and facing … the true truth — to really face what the truth is, and then work for change.”

The Rev. Jim Wallis — the inaugural holder of the Chair in Faith and Justice and leader of the Center on Faith and Justice in the McCourt School of Public Policy at Georgetown University — reminded the audience that in the Bible, there are two kinds of time: chronos, “tick-tock, tick-tock, normal time” and kairos, “a time that changes time — events that will change things for decades or generations.”

“We’re now at a kairos time. This election cycle is not normal,” Rev. Wallis cautioned. “Kairos, this time, will change so many things — and I’ll just be clear. White supremacy is making a last stand, by any means necessary, to retain white minority power in this country,” he said. “And so we’re not up against how much progress have we made. We’re seeing people who want to turn back everything, even prior to 1964.”

“We’re in a battle for — I call it the ‘imago Dei’ movement — whether or not we’re all made in the ‘image of God,’ or not,” Rev. Wallis continued. “And every effort to suppress a vote; deny a vote; not count a vote; intimidate a vote; is an assault — literally — on imago Dei; the image of God. … And what we all do — not just talk tonight — we all do in the next five months is crucial to the future of this country for generations to come.”

“I grew up with 1964, with the Civil Rights Act,” said Kessley Janvier, a rising senior at Georgetown University who serves as the vice president of Georgetown’s Black Student Alliance and the Georgetown chapter of the NAACP. “And everything that I learned, all the way through elementary school, about equal rights, and equal housing, etc. — it all came crashing down at — I want to say 13, 14 — when I realized yes, this legislation is the baseline, but it’s not the reality.”

She added, “And so, we can have it on the books — but I can tell you that. … It’s made, yes, a difference. But that difference is limited.”

Janvier said that she and other students carry not only their full course loads but also demanding advocacy responsibilities.

“I think it says enough about the progress that we’ve had as a society,” Javier concluded.

“For me, yes, we have made progress,” said Diann Rust-Tierney, executive director of the Racial Justice Institute at Georgetown University, former executive director of the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty and former legislative counsel at the American Civil Liberties Union. “Our presence on this stage in these very different roles is evidence of that. But it’s also a reminder of the recalcitrance with which the effort to really make this an equal society has been met, consistently.”

Rust-Tierney recalled that the 13th and 14th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution — which abolished slavery and addressed citizenship rights and equal protection under the law — were intended to transform the state of equality in America.

“We are at this point because we have not confronted the underlying problem: What kind of country are we going to be?” Rust-Tierney asked. “Are we going to be a country committed to equality — to sharing power with everybody — or are we going to be a country that’s committed to this project of a racial hierarchy?”

This article was written by Kimberley Heatherington who writes for OSV News from Virginia.

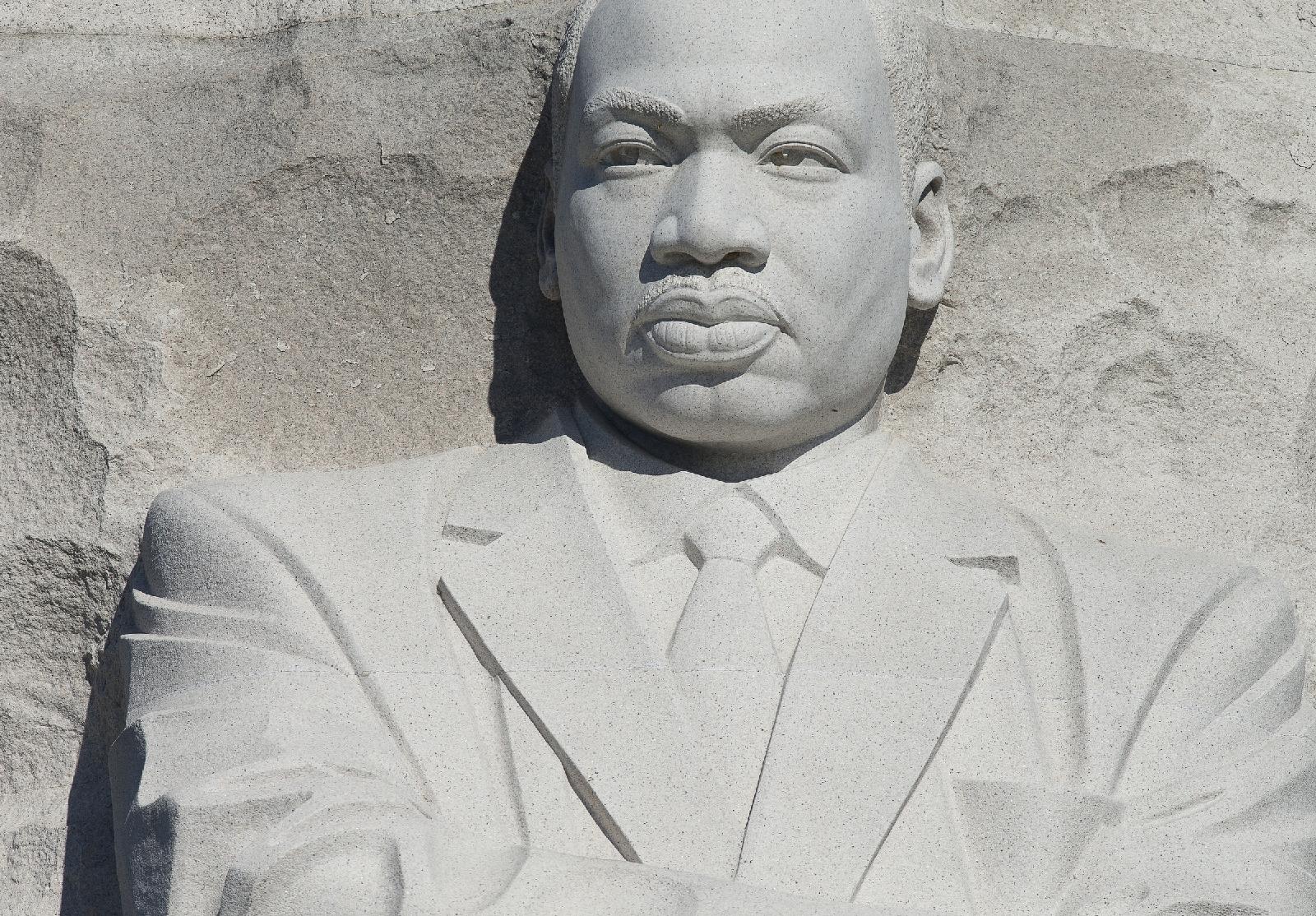

Featured image: The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial in Washington is seen Oct. 2, 2017. This year the federal holiday marking the birthday of the slain civil right’s leader is Jan. 15. (CNS photo/Tyler Orsburn)