Looking back at 150 Years of American Catholic life in new book on Seton Hall University

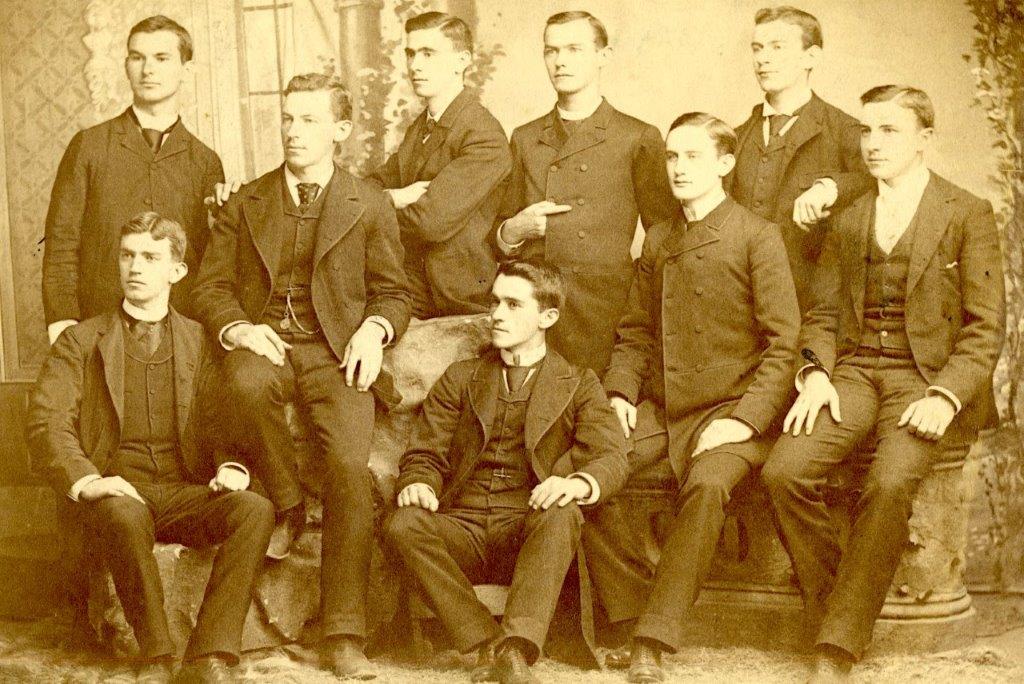

Dermot Quinn, D.Phil., professor in the Department of History, College of Arts and Sciences, and the editor of The Chesterton Review, presents a wealth of scholarship through the fascinating lens of the men and women who helped shape an educational institution in in his latest book, Seton Hall University A History, 1856-2006. Published on Feb. 10 by Rutgers University Press, Quinn’s book vividly examines how the University developed from very modest beginnings to a major national Catholic university. Selecting often personal stories during significant national and global moments, he follows these episodes of triumph and tragedy through the vision and deeds of the University’s founder, Bishop James Roosevelt Bayley, who established Seton Hall during a time of prejudice, and the many men and women who helped carry that vision forward.

Quinn was educated at Trinity College, Dublin, and received his doctorate at New College at the University of Oxford and is the author of several books including The Irish in New Jersey: Four Centuries of American Life, Rutgers University Press, 2004; Patronage and Piety: The Politics of English Roman Catholicism, 1850-1900Stanford University Press/Macmillan, 1993, and Understanding Northern Ireland, Baseline Books, Manchester, UK, i 114, 1993.

Quinn undertook this project at the request of Monsignor Robert Sheeran, who asked Quinn to write the University’s history to commemorate the University’s sesquicentennial as a companion volume to Monsignor Robert James Wister’s Stewards of the Mysteries of God Immaculate Conception Seminary, 1860-2010.

In the words of the publisher, Quinn “paints a compelling picture of a university that has enjoyed its share of triumphs but has also suffered tragedy and loss. He shows how it was established in an age of prejudice and transformed in the aftermath of war, while exploring how it negotiated between a distinctly Roman Catholic identity and a mission to include Americans of all faiths.”

In Case You Missed It: Lawyers, judges celebrate Red Mass (Photos)

Quinn explains that his history reflects a number of themes, one of them how a very small college became a very large and distinguished university. He also says that the Seton Hall story touches many other stories: “It is the story of New Jersey. It is the story of higher education in America. It is the story of immigration. It is the story of American and global Catholicism.”

Founder Bishop Bayley so much admired the spiritual and educational legacy of his aunt, that he named the college after her.

“It was a tribute to an extraordinary woman. He wanted something of her spirituality, something of her dedication, something of her commitment to those who had been left behind to shine through the college that he founded. So she is, if you like, the unseen presence of the story because it was Bayley’s efforts to commemorate her, not simply in a name, but in action that made Seton Hall what it was, and what it continues to be. If you look at New Jersey in 1856, it was not hospitable to the Catholic Church. Bayley was very keen with the growing population of Catholics in New Jersey that they should be educated.”

“This is a really kind of rich human story. What strikes me is that we sometimes use and overuse the term the Seton Hall family. But I am struck by the kind of deep wellspring of affection for Seton Hall, and I think that by and large, that affection has been earned because Seton Hall actually does nurture people. It does care for people. People have made enormous sacrifices, especially priests. That was true at the beginning of Seton Hall’s history and it remains true today,” reflects Quinn.

The opening lines of Quinn’s book set the scene:

In 1856 James Roosevelt Bayley, Roman Catholic Bishop of Newark, founded a school in Madison, New Jersey, calling it Seton Hall College in honor of his aunt, Elizabeth Ann Bayley Seton. The name was a gesture of piety and a statement of intent. By honoring the greatest promoter of Catholic schools in early nineteenth century America, Bayley wished to continue her work of building American Catholicism through education, charity, and moral instruction. The new school was thus, in various senses, an act of faith. In the first place, it kept faith with a remarkable woman. In the second place, it promoted a particular faith, Roman Catholicism, and a particular people, the Catholics of New Jersey. Seton Hall was to cater for a new flock spiritually and socially, giving it a place in the world and, perhaps, in the world to come. “The school-house has become second in importance to the House of God itself,” he wrote shortly before he became bishop in 1853. “We must . . . imbue the minds of the rising generation with sound religious principles.” As Catholicism took root in America, it needed such practical theologies of bricks and mortar. Bayley’s diocese, only three years old in 1856, was mission territory. His people were poor, unsophisticated, and unlettered, mainly immigrants and laborers with a handful of businessmen and professional people thrown into the mix. Immigrants held to their Catholicism as a living faith or as a diminishing memory of the world they had left behind. Not much higher up the social scale, business people were also condescended to by Protestants. It took imagination and courage to see in this unpromising terrain a future harvest. Bayley had both. Seton Hall was the seed and fruit of his vision. In the thin soil of mid-Victorian New Jersey Catholicism, he built more than a school. He built a people.

Among the many celebrities who attended Seton Hall, were actors Lionel and John Barrymore. Quinn describes them in Chapter 4 of the book:

Lionel remembered Seton Hall as “among the happiest days of my life,” marked, in his case, by almost complete absence of scholastic achievement. Most of the time was spent in the gym. John tried out the parallel bars and several odd items fell from his pockets including a set of brass knuckles, a pack of cigarettes and a half pint of cheap whiskey.” It was at Seton Hall where he heard “the most amazing understatement of all time”: “There was a football player who was unfortunately required to go to class. One morning, our instructor, forgetting to treat the great with proper consideration, called on this athlete and demanded of him that he give a short talk on the music of Robert Schumann. Our hero arose, shifted from one foot to the other, looked desperately about, and uttered this classic: “Well, Schumann, this Schumann, well, he was all right.” And sat down.

In Chapter 10, A New Beginning, Quinn reflects on what the campus looked like in the 1940s.

To the casual visitor, Seton Hall in 1945 looked like a college from an earlier time. It was small, rustic, faintly dilapidated, a place with few residents (sixty in 1940) and even fewer prospects. Only the extension campuses showed signs of life. South Orange was moribund. “There was no such thing as a gate,” remembered William Dunham, appointed to teach political science at the end of the war, “merely a narrow road, half dirt, half paved, only big enough for two cars.” A tree-lined path formed an arch from the entrance on South Orange Avenue to the Administration Building, the chapel, Bayley Hall, the Preparatory School (in Mooney Hall), Alumni Hall, the Marshall Library, and the gymnasium. Seton Hall was mostly grass and fields, one of hundreds of small colleges built for the nineteenth century and unsure of how to cope with the challenges of the twentieth. Its virtual abandonment during the war, except for summer schools and a handful of students and priests, gave it the appearance of a gothic morgue. The war had shown Seton Hall’s decency, bravery, and improvisation, but also—in Kelley’s efforts to make ends meet, in his warning that technology would make or break small colleges, in his uncertainty about state support for private education—its challenges and limitations. Unless numbers picked up, the future was doubtful. Even if they did pick up, the future would be different from the past.

Reviewing the book enthusiastically, historian and author Terry Golway described it as “An insightful piece of cultural history, explaining how Catholics built their own institutions, debated among themselves how these institutions served a greater good, and struggled to grow and adapt their schools to a more secular age. The scholarship is profound.”

Augustine J. Curley, OSB, of the New Jersey Catholic Historical Commission and the Benedictine Abby of Newark says that “Quinn deftly tells the story of Seton Hall University, gracefully elucidating the struggle to remain faithful as a Catholic institution while seeking a place among the great universities of the United States. Seton Hall University is a story that mirrors that of the Catholic Church in New Jersey and, indeed, in the nation.”

A book signing and launch event is forthcoming in the Spring 2023 semester. To learn more, please visit the book’s listing on the Rutgers University Press website.