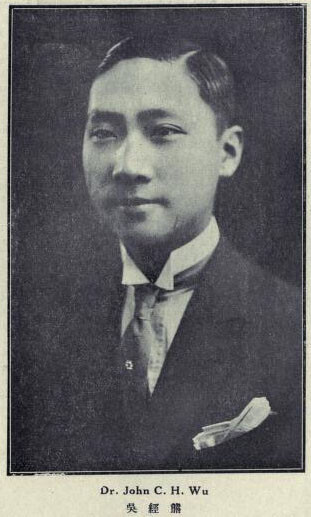

John Wu: The quiet scholar whose work is known around the world

During the month of May, we observe Asian and Pacific Islander Heritage Month. Sadly, recent months have witnessed terrible acts of violence toward our Asian and Pacific islander brothers and sisters. I wish to share with you a story of a great Asian Catholic scholar who graced the Archdiocese of Newark with his presence and wisdom for many years. His name was John Ching Hsiung Wu.

In the 1960s, students arriving in early morning at Seton Hall University saw a tall and distinguished man purposefully striding across the campus toward the University Chapel. He always wore an ankle-length traditional Chinese silk robe and was followed a few paces behind by his loving wife.

New students would ask: “Who are they? Where are they going?” They would be told that they were “Dr. Wu and his wife. They are going to the 8 a.m. Mass. They go to Mass every day.” Further investigation would uncover that this was no ordinary person.

Actually, Dr. Wu was an internationally renowned lawyer and jurist. He wrote scholarly books and articles in Chinese, English, French, and German. Many of his topics were in the realm of law. He was, after all, a professor at the Seton Hall Law School. He loved the law and its great practitioners. He carried on a multi-year correspondence with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes (1841-1935), published in Justice Holmes to Doctor Wu: An Intimate Correspondence 1921-1932.

But he went far beyond the law. He also wrote on Chinese literature, including a translation of the Tao Te Ching, an eighth-century Chinese classic attributed to Lao Tzu, the founder of philosophical Taoism, considered by many of his followers to be divine.

While in Law School in Shanghai, he was baptized a Methodist. In 1937, after reading the biography of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux, he converted to Catholicism. What led him to the Church? Let us read his own words, in the preface to The Science of Love – A Study in the Teachings of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux.

I heard the name of Thérèse of Lisieux for the first time at the home of my dear friend, Mr. Yuan Kia-hoang, a most zealous Catholic. In the Winter of 1937, I was living in Mr. Yuan’s house, and I was impressed by the way the Yuans recited their family Rosary. Seeing a portrait of Saint Thérèse, I asked him, “Is this the Virgin Mary?” He told me that it was the “Little Flower of Jesus.” “Who is this Little Flower of Jesus?” I asked. He looked surprised and said, “What? You don’t even know Saint Thérèse of Lisieux?”

Then he gave me a French pamphlet entitled “Ste. Thérèse de ‘Enfant-Jésus,” which contained a short account of her life and many specimens of her thoughts. Somehow, I felt those thoughts expressed some of my deepest convictions about Christianity which I happened to entertain at that time. I said to myself, “If this saint represents Catholicism, I don’t see any reason why I should not be a Catholic.”

Being a Protestant, I was free to choose whatever interpretation suited best my own reason, and her interpretation was exactly the right one for me, and that made me a Catholic!

Wu later wrote The Interior Carmel – The Threefold Way of Love. Here he demonstrated that mankind could live in the world with the spirit of the cloister. Wu believed that we were all born to be saints and that the seeds of sanctity are at hand for planting, nurturing, and ripening. These themes he developed under the titles: “The Budding of Love,” “The Flowering of Love,” and “The Ripening of Love.” Unique in this work is the clear influence of the Chinese classics so familiar to Wu and his mastery of several Western Christian mystics, including Saint John of the Cross.

His spiritual growth was further stimulated by a lengthy correspondence with Thomas Merton from 1961 to 1968. This correspondence covers 178 pages in the Merton Archives. It was published in The Hidden Ground of Love: Letters of Thomas Merton. Wu was Merton’s principal guide to the development of Merton’s interest in and fascination with Asian spirituality. Their dialogue can be read in Merton & the Tao: Dialogues with John Wu and the Ancient Sages in The Fons Vitae Thomas Merton Series.

When he was not writing, Dr. Wu lectured at Harvard University, the University of Paris, the University of Berlin, and the University of Michigan, to name a few. He also was the principal author of the constitution of the Republic of China (Taiwan), an adviser in the Chinese delegation to the 1945 United Nations Conference on International Organization in San Francisco, the Chinese ambassador to the Holy See in 1947-49, a judge of the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague.

After the Communists came to power, Dr. Wu came to the United States with his family and assumed the post of professor at Seton Hall Law School in 1951. He remained at Seton Hall until he retired and returned to Taiwan in 1967.

A quiet and always dignified scholar, Dr. Wu lived a spiritual life that was hidden to most. His devout attendance at daily Mass and the profundity of his spiritual writings demonstrate a humility and quiet serenity that touched many throughout his life.

In 2016, in observance of the 30th anniversary of his death, Catholic Studies at Seton Hall University hosted a two-day seminar on Dr. Wu. The papers of that seminar are currently being edited. It would be a beautiful thing if his life and writings were even more deeply studied.

John Wu transcends many barriers. His jurisprudence and his commentaries on Chinese Law and Common Law today are studied in the law schools of the People’s Republic of China. He did not neglect the natural law, which he analyzed in his work, Fountain of Life. His mastery of Chinese and Western spirituality allowed him to make both part of his life, blending them but not losing the uniqueness of either. We gain a glimpse of this great achievement in his spiritual autobiography, Beyond East and West.

Such accomplishments can serve as a bridge between two cultures that often seem to be so far apart. I believe that Dr. Wu and his life and work could be a catalyst to bring them closer together. His love for the law and for scholarship also can serve as an inspiration to lawyers and scholars, especially those who seek to join their professional vocation to their spiritual life.

John Wu took great pride in his family. He was the father of thirteen children. As a minor seminarian, on many occasions I was privileged to hold the paten under the chin of this humble and kind man when, together with his wife, he received the Eucharist in the Chapel of Seton Hall University. I look forward to a day when the life of this unique man is brought to the attention of Church authorities who will find him worthy not only of imitation, but of veneration.

Msgr. Robert J. Wister, Hist.Eccl.D. is a retired professor of church history at Immaculate Conception Seminary School of Theology, Seton Hall University, and writes historical articles for the publications of the Archdiocese of Newark.

Resources: